By Howard Marlowe

With the recent Senate passage of its version of the Water Resources Development Act (WRDA) of 2016, and possible House passage before the end of the year (if not by the end of this month) it’s a good time to look at what lies ahead in 2017. To do that, however, we really need to get a handle on the realities that face everyone in the water resources community that depends on Federal policies or funding.

The current system for constructing and maintaining all types of water resource projects is largely a creature of significant reforms enacted by Congress in 1986, which in turn are based on a Federal commitment to build ports and navigation channels that owes its origins to the mid-19th century. What was once a strong interest of Congress, has now lost much of its enthusiasm. While some say that is the case for all infrastructure, the fact is that water resources are the nation’s silent infrastructure. Most of us who enjoy its benefits don’t even realize how much we rely on water to transport raw and finished goods to domestic and foreign markets, let alone dams to protect us from floods, and navigation channels for both commercial and recreational boating. Some federal projects are also designed to prevent storm damage and coastal flooding using sand dunes and wetlands, as we have seen in Louisiana and post Superstorm Sandy.

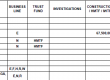

There are several things that set apart the Federal investment in water resources from surface transportation (highways and railroads) and aviation. Water resource investments are managed by the Army Corps of Engineers. The Corps is not a grant-making agency, nor does it decide where projects get built. Until a few years ago, a local or state government made its request for a new or modified project to its congressional delegation, which then triggered a process that is pictured in this chart. Without congressional earmarks, that request is now made to the Assistant Secretary of the Army, who decides whether it moves any further. But the Corps is not a grant-making agency. Instead, the Corps does all the planning, engineering, and environmental work. It also does some of the construction work and supervises all of the rest. The state or local government is the cost-sharing partner with the Corps but it doesn’t get control over any of the Federal money. Its cost-share is provided to the Corps in the form of a check or approved in-kind services.

I have used the word “project” several times already, which gets to the heart of why the current system is outdated. We use WRDA bills to authorize studies and then (many years later) to authorize them as projects if they meet Federal standards (adopted in 1983). They get funded (if at all) through separate appropriations bills where the President’s earmarks are allowed but those from Congress are prohibited. The Corps of Engineers has been on the sh***list of every Administration since Jimmy Carter, who definitely did not have a happy experience as governor of Georgia with the Federal agency in charge of water resource projects. Congress, is now reduced to adding pots of money for different types of water resource projects, which are then allocated by the same Administration that didn’t ask for any more money in the first place.

Focusing on the coast, which for nearly 40 years has been my special interest, I have seen how one Administration after another has tried to kill the very projects that Congress has authorized to provide protection to people and reduce damages to property and infrastructure caused by storms and sea level rise. The culprit is the White House Office of Management and Budget. Instead of investing $1 in dunes and wetlands in order to get $2 to $4 in reduced storm damages, they will do their best not to spend that $1 and then find they have to spend $10 or more in storm damage repairs and assistance. Until Congress as a body wakes up and takes back its power to spend money on studies and projects that have been authorized, the career bureaucrats at OMB will get their way. My college course in bureaucracy taught me that a smart bureaucrat can have more power than the Congress and the President combined. For the nation, all the Corps’ coastal resilience studies and projects get a mere $80 to $100 million a year. You could build one commercial jetliner or two highway interchanges for that price. In fact, the non-disaster coastal resilience needs for authorized studies and projects are more than three times that figure.

Water resources projects are part of a system. They relate to each other and need to be managed that way. Focusing on the coast, beaches and ports, navigation channels, and environmental resources are related to each other. If you fix a problem occurring with one component, you may create a bigger problem with another. The answer is called a Systems Approach, or just plain Regionality.

In future posts, I’ll talk more about that and also get into the details of a 19th century process that has got to be overhauled. In the meantime, please send you comments to Waterlog@aldenst.com.

* The opinions expressed are mine and do not necessarily represent any client or organization with which I am associated.